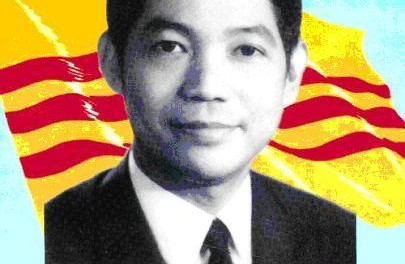

Dr. Huy, the Gandhi of Vietnam – Hon. David Kilgour

Nguyen Ngoc Huy, the Mahatma Gandhi of Vietnam

Hon. David Kilgour

City of Westminster, California

30 July 2011

Over half-a-century, Nguyen Ngoc Huy (1924-1990) became a giant among those across the world seeking a democratic Vietnam, so much so that he earned the title “the Gandhi of Vietnam”.

Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948) brought the United Kingdom, then one of the world’s

most powerful nations, to its knees by using peace, love and integrity as his methods of

change.

Huy made major contributions to the evolution of Vietnam- albeit certainly delayed since

1975- towards multiparty democracy, human rights and the rule of law.

Leaders should not be judged only by the success or failure of a particular goal. India is

now free. Vietnam still languishes in totalitarianism, but both Gandhi and Huy were

exemplary leaders of the 20th century.

One of Huy’s books, Survival of a Nation, was described by Nguyễn Cao Quyen, the former

judge and prisoner of war, as presenting a system of governance combining the principles

of democracy successful in Western civilizations with the unique characteristics of

Vietnamese culture. “Had (Huy’s) principles been applied to Vietnam following the

departure of the French in 1954,” he added, “or after President Ngo Dinh Diem’s

assassination in 1963, there might not have been a Vietnam War.”

Nguyễn Ngoc Bich, chair of the National Congress of Vietnamese Americans (NCVA), has

noted that, in addition to his political legacy, Prof. Huy left “an enormous body of scholarly

writings that would take future generations years to absorb.”

Gandhi’s goal was to set India free and to fight for the rights of repressed communities of

Indians through non-violent means. Martin Luther King Jr., said, “Christ gave me the

message; Gandhi gave me the method.”

At 21, Huy went to work at Vietnam’s National Library, where he ‘devoured books’ and

wrote articles on youth, politics and poetry. He composed the “Unknown Hero”, which

was first recited in the schools and later sung to honour fallen soldiers. When suppressed

by the authoritarian Ngo Dinh Diem government in the ‘60s, Huy took refuge in Paris,

where he continued his studies while working at odd jobs. In 1963, he earned a Ph.D. in

political science at the Sorbonne.

Self-Discipline

Gandhi believed that continuously challenging his self- discipline improved his

commitment to achieving his goals. He was focused always. He “would free India or die in

the process.”

Huy was similarly self-disciplined. Bui Diem, South Vietnam’s ambassador to America in

the 1960’s, noted “… a special trait of his personality that was so persistent that it became

dominant over his whole political life. He was devoted to the idea of reform at every stage

of his political activities and he consistently tried to put that idea into practice.”

Gandhi’s convictions were the most important factor in his success. He had the ability to

inspire the Indian people to believe in themselves and their goal of freedom. One of his

strongest beliefs was that “willpower overcomes brute force”.

A Vietnamese researcher on Huy’s life noted, “Dr. Huy’s passion for his mission touched

everyone, young and old alike. His charisma transcends frontiers and races. Like the myth

of Sisyphus, Dr. Huy struggled uphill to build a democracy for Vietnam… His determination was a fire that lit people up like a lighthouse and guided thousands of us…”

Relating to People

When Gandhi spoke to large audiences, listeners felt he was speaking to them individually.

Huy related to many as inspirational poet, professor, politician and author. His literary

output included over twenty books in Vietnamese, French and English; seven monographs;

nine lectures delivered at universities in Vietnam and the U.S.; a book of 115 poems. His

academic home after South Vietnam fell in 1975 until his death from cancer in 1990 was as

a research scholar at Harvard University.

At times, Gandhi had to be flexible to counter British tactics. In exile in France, Huy also

had to compromise. Encouraged by his wife to continue his education, he relinquished his

role as the family’s main breadwinner. Their daughter, Nguyễn Ngoc Thuy Tan, remembers

her mother as an “unknown hero” from that period.

Transcending Adversities

The first time Gandhi rose to speak in court, he could not utter a single word due to

fear. This early humiliation drove him to become on e of the best public speakers of all

time.

For his part, Huy returned to Vietnam and went on to hold various high-level government

positions and to teach at a number of Vietnamese universities. He wrote numerous

newspaper articles, seeking to promote democracy and motivate youth to become active in

politics. He collaborated with Dr. Ta Van Tai of Harvard and Tran Van Liem, the former

Chief Justice, on a three-volume code of Vietnam jurisprudence.

Integrity

Gandhi would accept no deviation to the principle of non-violence. He would rather go to

jail (and often did) rather than go back on his word about non-violence.

The Alliance for Democracy in Vietnam (ADV) was for med in the U.S. in the early 1980s. Dr. Huy, with only one dark suit and contributions from his supporters, went around the world several times to educate and recruit many Vietnamese who became members of ADV.

Huy’s message was always non-violence as well. He realized that, since Vietnamese

refugees from totalitarianism were dispersed across the world with no military and limited

financial resources, they had to rely on others to exert leverage on the party-state in Hanoi.

Leadership styles Gandhi promoted love and peace in times when another leader would have made a call to arms. So did Prof. Huy.

In 1986, Huy founded the International Committee for a Free Vietnam (ICFV) with the

support of European, American, Canadian and Australian legislators. Serving as honorary

members, we parliamentarians committed ourselves towork for the restoration of human

rights and basic liberties absent since 1975 in Vietnam. Many of us came to know and love

Dr. Huy during his travels in the 1980s.

Need I say more about describing Dr. Huy as “The Gandhi of Vietnam?”

In closing, permit me to make some comments on the human dignity, governance and

economics in Vietnam today, mostly drawn from the Economist Intelligence Unit July 2011

Country Report.

Human Dignity

The party-state in Hanoi continues to exploit approximately 86 million Vietnamese in the

same manner as when it seized South Vietnam in 1975. No-one but the party-state in

Hanoi knows how many prisoners of conscience there are today, but the following are

representative of those in its gulags or facing persecution.

Minorities in the central highlands, known as Montagnards, face harsh persecution. This

spring, Human Rights Watch (HRW) reported that the regime had intensified its repression

of Montagnard Christians pressing for religious freedom and land rights.

Father Thadeus Nguyễn Văn Lý, calling for a democratic election and a multiparty state,

was sentenced to eight years imprisonment in 2007. He subsequently suffered two strokes and was released into home detention on condition that he return to prison to serve out his sentence. Unfortunately, he appears to be again now in custody.

Unified Buddhist Church Supreme Patriarch Thích Quảng Độ has been confined without any

charge in his monastery for years under police surveillance. Four Hòa Hảo Buddhists were

sentenced in 2007 to prison for protesting the imprisonment of other Buddhists. Cao Đài

members were in 2005 sentenced to up to 13 years in prison for delivering a petition calling for religious freedom.

Ms Le thi Cong Nhan is a Hanoi-based human rights lawyer who was jailed in May 2007 for four years for “conducting propaganda against the state.”

Phạm Thanh Nghiên did advocacy work on behalf of landless farmers. In 2010, she was sentenced to four years in prison followed by three years under house arrest on charges

of spreading anti-government propaganda.

Catholic priest Peter Phan Văn Lợi has been held under house arrest without any charge. The Hmong Protestants in the northwest and the Khmer Krom Buddhists in the Mekong River delta also face persecution.

Trần Khải Thanh Thủy, the well-known novelist, has played a key role in the democracy

movement. In 2010, she was sentenced to 42 months in prison.

Lê Công Định spoke up for bloggers, human rights defenders, and democracy and labour rights activists. In 2010, he was convicted of ‘attempts to overthrow the state’ and sentenced to five years of incarceration.

Nguyễn Tiến Trung, in his twenties, while studying in France, established the Youth Assembly

for a Democratic Vietnam, and later met with the president of the Council of Europe, Prime Minister Harper and many other democratic leaders. Returning home, he was drafted into the army and later sentenced to seven years for advocating democracy.

Lawyer Trần Quốc Hiền defended farmers whose land was confiscated and published articles online. In 2007, he was sentenced to five years imprisonment and two years house arrest on release for ‘spreading anti-government propaganda’ and ‘endangering state security’.

Nguyễn Hoàng Hải ( Điếu Cày) is known for hard-hitting internet postings calling for greater democracy and human rights and for participation in protests against the Chinese party-state foreign policy. In 2008, he was sentenced to 30 months in prison on tax charges.

Cù Huy Hà Vũ, legal scholar, government critic and dissident, was sentenced to seven years in prison on anti-government propaganda charges in 2011 following the country’s most-high profile trial in decades. He will reportedly be retried next month, although the identical result appears to be pre-decided.

Until the party-state improves its record, Human Rights Watch calls on the Obama administration to reinstate the designation of Vietnam as a Country of Particular Concern

(CPC) for violation of religious freedoms. (http://www.hrw.ore/en/news/2010/03/24/testimony-sophie-richardson-tom-lantos-human-rights-commission shows how to find HRW’s recommendations as to how governments can respond effectively to the abuses suffered by Vietnamese human rights defenders.)

Political Outlook

Counter-intuitively, the Economist predicts the Vietnamese party-state will continue to

strengthen ties with the West. Military links with the U.S. have become closer, as indicated

by joint military exercises in the South China Sea in August 2010. American concerns over

human rights and religious freedom remain a major source of bilateral tension. Matters are

further complicated by President Nguyễn Minh Triết seeking to maintain warm relations

with the Party in China.

Economy

The real GDP growth is forecast to slow to 6% for the year. Inflation will accelerate to an

average of 18.8%, causing weakened private consumption and investment growth. Price

hikes of this magnitude cause severe pain to families and can quickly escalate to

hyperinflation. Pressure to tackle the persistently wide trade deficit also continues.

Corruption is a major and growing problem. The Next Generation Conference was told

yesterday in Orange that about three quarters of Vietnam’s people live in rural areas, where

incomes are approximately 40 percent of what urban residents obtain.

Conclusion

The life of Nguyễn Ngọc Huy was exemplary to the point that the Vietnamese Diaspora and

many others might pledge to follow his teachings on human rights and democracy until the

end of our lives.

Today the Alliance for Democracy in Vietnam and the International Committee for a Free

Vietnam, inspired by Dr. Huy, work hand in hand to produce resolutions that call for

Vietnam’s party-state to free prisoners of conscience, open up fair trade with other

countries, allow multiple political parties, and conduct free and transparent elections.

We all know that if Dr. Huy or his followers governed Vietnam today, having won office in

a free and fair election, the governance of the Vietnamese people would be most different

today. Let us re-energize our work around the world to make democracy a reality in

Vietnam.

Thank you.